Specific immunoglobulins are preparations that contain a high concentration of antibodies to particular viruses or bacteria or in the case of Anti-D, high concentration of antibodies to Rhesus Factor D (RhD).

If they are given soon after exposure to the virus or bacterium concerned (e.g. soon after being bitten by a rabid animal), they will help to fight infection. This is particularly important in cases, where the affected person has not previously been vaccinated against the virus or bacterium. In such cases, it takes several days before the patient’s own immune system produces effective antibodies; specific immunoglobulins can help provide protection (usually lasting a few weeks).

Human tetanus immunoglobulin

Tetanus is an acute disease of the nervous system induced by the neurotoxin (poison) from the tetanus bacterium, Clostridium tetani. It is caused when the bacterium Clostridium tetani gets into the body, through a puncture wound in most cases. The bacteria grow in the wound and produce a very powerful poisonous toxin. The first symptoms are stiff muscles near the wound followed by spasm of other muscles; historical descriptions include stiffening the jaw muscles until it is locked in position (“lockjaw”). This is followed by frequent and painful fits. The muscle spasms can interfere with breathing. Anyone who is not fully protected against tetanus is at risk from the disease which can kill. The treatment for tetanus is very difficult so prevention is the main approach.

Tetanus is rare in the UK because of the immunisation programme, the main preventative approach. While vaccination has largely diminished the incidence of tetanus in Europe since it was introduced in the 1950s, it has not disappeared. Tetanus immunisation was provided to the Armed Forces from 1938 and therefore a large percentage of the elderly male population is immune. Those most at risk are elderly women.

In the UK, vaccination against tetanus infection is part of the childhood immunisation schedule. The first dose is given to babies at 2 months old followed by two additional doses at one-month intervals. Booster doses are also given at age 3-5 years (3 years after the primary course) and at age 13-18 years. Booster doses in addition to 5 doses is not recommended except in the case of the treatment of a tetanus-prone wound.

The following are considered tetanus-prone wounds:

- Any wound or burn that requires surgical intervention that is delayed for more than 6 hours.

- Any wound or burn at any interval after injury that shows one or more of the following: significant degree of dead tissue, puncture-type wound, contact with soil or manure (both likely to harbour tetanus organisms) and any clinical evidence of sepsis.

Human tetanus immunoglobulin contains antibodies against tetanus. It is given to certain groups of patients with tetanus-prone wounds to help them fight the infection straightaway. It is often given in hospital Emergency Departments to patients with certain types of injuries.

Human hepatitis B immunoglobulin

Hepatitis B immunoglobulin (HBIG) is given as a prophylactic measure to people at increased risk of exposure to hepatitis B virus.

Hepatitis B is caused by a virus that attacks the liver and causes it to become inflamed. It is estimated worldwide there are 800 million people infected with the virus and a further 300 million are carriers. People may have no symptoms at all but can still pass on the virus to others. Symptoms can include: itchy skin, weight loss, a short, mild flu-like illness, jaundice (yellow skin and eyes), loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea. It is possible to have contracted hepatitis B and not have symptoms for many years until it develops into long-term disease.

Hepatitis B can be passed on in the following ways: during sex with an infected partner, from an infected mother to her newborn baby during delivery, by users of injected drugs who can infect others through sharing needles, and through a blood transfusion in a country where blood is not tested for the hepatitis B virus. All blood in the UK is screened for hepatitis B. If you have had other types of hepatitis, you can still get hepatitis B. People who have had hepatitis B but haven’t recovered fully can remain infectious all their lives.

Hepatitis B can cause long term infection that leads to liver disease such as cirrhosis or cancer which can be fatal. 1.5% develop liver cirrhosis and 0.1% develop liver cancer. Hepatitis B is particularly likely to cause long term infection in babies and children. It is not known how many people are infected in the UK, but in some cities up to 1 in 100 women who visit antenatal clinics have been found to carry hepatitis B. Babies born to carrier mothers should begin with their vaccination as soon as possible after delivery (max. 24 hours).

Some healthcare workers inadvertently prick themselves with a used needle (‘needle-stick injury’) and are at risk of hepatitis B infection. Healthcare workers are usually vaccinated now to prevent this happening.

Specific hepatitis B immunoglobulin (HBIG) is available for passive protection and is normally used in combination with hepatitis B vaccine to confer immediate cover (passive immunity) and long-lasting protection (active immunity) respectively after exposure – post-exposure prophylaxis.

Whenever immediate protection is required, immunisation with the vaccine should be combined with the simultaneous administration of HBIG at a different injection site. It has been shown that passive immunisation with HBIG does not suppress an active immune response. A single dose of HBIG is sufficient for healthy individuals. If infection has already occurred at the time of passive immunisation, virus multiplication may not be inhibited completely, but severe illness and, most importantly, the development of the carrier state may be prevented.

Groups requiring post-exposure prophylaxis:

- Babies born to mothers, who are HBeAg* positive carriers, who are HBsAg** positive without e markers, or who have had acute hepatitis during pregnancy.

- Persons who are accidentally inoculated, or who contaminate the eye and mouth or fresh cuts or abrasions of the skin with blood from a known HBsAg** positive person.

- Sexual partners of individuals suffering from acute hepatitis B, and who are seen within one week of onset of jaundice.

*HBeAg stands for hepatitis B “e” antigen. This antigen is a protein from the hepatitis B virus that circulates in infected blood when the virus is actively replicating.

**HBsAg stands for hepatitis B surface antigen. When a healthcare provider orders blood tests to determine if someone is infected with the hepatitis B virus, one thing they are looking for is HBsAg in the blood. If it is found, along with other specific antibodies, it means the person has a hepatitis B infection.

Human Varicella-Zoster immunoglobulin

Shingles and chicken pox are both caused by the same virus of the herpes family known as Varicella-Zoster Virus (VZV). The word herpes is derived from the Greek word ‘herepein’, which means ‘to creep,’ a reference to the characteristic pattern of skin eruptions. VZV is still referred to by separate terms:

Varicella: the primary infection that causes chicken pox.

Herpes Zoster: the reactivation of the virus that causes shingles.

Chicken pox is a common childhood disease with symptoms of slight fever, physical discomfort, uneasiness and skin rashes that blister into itching sores which eventually scab. In adults, a chicken pox infection is more severe than in children; many infected adults can develop pneumonia.

Shingles is a reactivated disease that appears in older adults who were previously infected with the virus. The virus lies dormant in the spinal cord for years. When reactivated it affects the nervous system and causes inflammation of the nerve fibres of the skin. These are bundles of nerves that transmit sensory information from the skin to the brain. Here, the virus has properties that allow it to hide from the immune system for years, often for a lifetime. This inactivity is called latency. Shingles is more common after the age of 50 and the risk increases with advancing age. Shingles causes numbness, itching and often severe pain followed by clusters of blister-like lesions in a strip-like pattern on a section of one side of the body. The pain can persist for weeks, months or years after the rash and infection heals and is then known as post-herpetic neuralgia.

It is not clear why the virus reactivates in some people and not in others. In many cases, the immune system has become impaired or suppressed by aging, or exceptionally from immunodeficient diseases (e.g. AIDS) or from certain cancers or drugs that suppress the immune system.

Human Rabies immunoglobulin

Rabies is a highly contagious infection that attacks the central nervous system. It is caused by a virus that enters the body through the bite of an infected animal or through the contact of infected saliva on a cut or graze. The incubation period is usually between 30 and 70 days, although in some cases it can be as short as 9 days or as long as several months. The reason for this incubation time variance depends on the site of the original infection, i.e. a shorter or longer time it takes the virus to reach the spinal cord and brain. Not everyone who is bitten by an infected animal develops rabies. There is little treatment for rabies and once the disease has taken hold it is invariably fatal. If the disease is caught in the incubation period its development may be prevented. The wound or bite should be thoroughly cleaned and then human rabies IgG given. Rabies is very rare in the United Kingdom but is endemic in continental Europe. Vaccines are available to protect vets, farmers and others, whose occupations put them at risk from the disease. There is a specific vaccine available for domestic animals.

Rabies is a rhabdovirus that gets into the central nervous system via the nerves in the skin and surrounding tissues around the bite. The first symptoms are usually those of any flu-like illness (headache, sore throat, and fever), but there may also be altered sensation at the wound site, e.g. numbness, tingling or itching. It would be extremely difficult to diagnose at this point unless the person mentioned the possibility of a bite or other exposure to an animal. These early symptoms may last several days but then would progress to the symptoms most associated with rabies and which are caused by an acute inflammation of the brain (encephalitis). Symptoms include: mental disturbance e.g. confusion, anxiety, agitation, hallucinations; an increase in the amount of saliva causing the typical foaming of the mouth; spasm of the muscles, particularly those at the back of the throat when drinking water, hence the ‘fear of water’, unsteadiness and a lack of co-ordination; and eventually paralysis. These symptoms may last for 7-10 days and are followed by coma. Death is usually due to heart failure or to an inability to breathe (respiratory failure). There is no effective treatment once the neurological symptoms emerge. Supportive treatment is all that can be offered.

Pre-exposure prophylaxis. Pre-exposure prophylactic immunisation should be offered to those at high risk: laboratory staff who handle the rabies virus, such as those working in quarantine stations; animal handlers; veterinary surgeons and field workers who are likely to be bitten by infected wild animals; certain port officials; and licensed bat handlers. Human transmission of rabies has not been recorded but it is advised that those caring for patients with the disease should be immunised as if they have been exposed. Pre-exposure immunisation is also recommended for those living or travelling, usually for longer than 4 weeks, in areas where rabies is endemic, especially those who will be away from medical facilities or those who may be exposed to unusual risk. Pre-exposure prophylaxis is indicated during pregnancy if there is substantial risk of exposure to rabies. Pre-exposure use requires 3 intramuscular doses of rabies vaccine, with further booster doses for those who remain at continued risk.

Post-exposure prophylaxis. Post-exposure prophylaxis depends on the level of risk in the country, the nature of exposure, and the individual’s immune status. Specialist advice must be sought for all bat bites. There are no specific contraindications to the use of a rabies vaccine for post-exposure prophylaxis and its use should be considered whenever a patient has been attacked by an animal in a country where rabies is endemic, even if there is no direct evidence of rabies in the attacking animal. As a result of the potential consequences of untreated rabies exposure and because rabies vaccination has not been associated with fetal abnormalities, pregnancy is not considered a contra-indication to post-exposure prophylaxis.

The use of Human Rabies Immunoglobulin is specified in the World Health Organisation (WHO) guidelines for specific systemic treatment.

The RhD factor & Anti-D

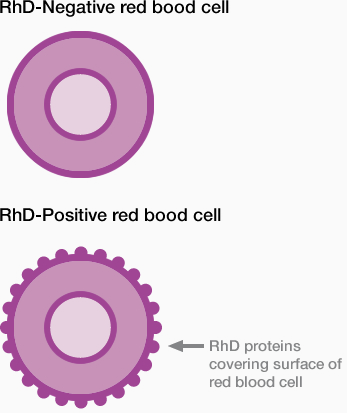

Pregnant women can often belong to different blood groups from their babies. This is perfectly normal and is usually not a problem. However, in about 1 in 10 pregnancies, these blood groups differ in one particularly important way: either the presence or absence of a protein on the surface of red blood cells. This protein was originally called the ‘Rhesus Factor’. It is now referred to as simply the RhD Factor.

If you carry this RhD Factor on your red blood cells, you are known as RhD Positive. If you do not, you are known as RhD Negative.

Sometimes, a small amount of blood can cross over from the baby’s circulation in the placenta and enter the mother’s blood stream. This can happen at any time in pregnancy, but most importantly during the last 3 months of pregnancy if there is a trauma of some kind, and just before birth. It can also occur at the time of a miscarriage or termination of pregnancy.

If this transfer of blood occurs from a RhD Positive baby to a RhD Negative mother, then the mother’s immune system will see the baby’s red blood cells as “foreign” and will produce antibodies to get rid of them, but only in the mother’s circulation.

The mother’s immune system retains the memory of how to make these antibodies, which gives her the ability to make them more quickly and in greater numbers in the future if required.

This generally only becomes a problem during a later pregnancy if the baby is again RhD Positive and there is another transfer of some of the baby’s red blood cells across the placenta. The mother’s immune system uses its memory to make the same antibodies as before but in quicker and in larger amounts. These can then cross the placenta into the baby’s circulation and start to destroy the baby’s red blood cells before birth.

Babies who have this problem are said to have Haemolytic Disease of the Newborn, or HDN for short.

Gaining protection from Anti-D

Doctors, nurses and midwives are very aware of this problem and can prevent it from happening by giving the mother an injection of immunoglobulin – or ‘Anti-D’. This can rapidly remove any RhD positive red blood cells which pass from baby to mother before they trigger the mother’s immune system to produce anti-D. This prevents the mother’s immune system developing a ‘memory’ for RhD positive red blood cells and later development of HDN in an unborn baby.

Anti-D works by destroying any RhD positive blood from the baby present in the mother’s circulation before she can make her own antibodies. This means that the mother does not have the antibodies available to cause HDN in any future pregnancies with an RhD positive baby.

Anti-D is made from a part of the blood called plasma that is collected from donors who have large amounts of anti-D antibodies. It is only from this specific collection of donors that anti-D can be produced: other immunoglobulins do not contain anti-D antibodies. The production of Anti-D immunoglobulin is very strictly controlled to ensure that the chance of a known virus being passed from the donor to the person receiving the Anti-D is very low – it has been estimated to be 1 in 10,000 million doses (i.e. 1 in 10,000,000,000 doses).